a. Critique of Comparative Methodology

a. Critique of Comparative Methodology

In this article, Joel Willitts [1]will seek to show the Letters of the Apostle Paul and the Gospel of Matthew share a, “basic theological affinity.” In his opinion, before a scholar may embark on comparing Paul and Matthew, one must pause to consider the obstacles which accompany this task. He claims that such an endeavor is of the highest order (here I assume he is referring to Bloom’s taxonomy for the term “higher”), synthesis, and much caution and reflection is required in accomplishing such a comparison. After the scholar has reflect on the arduousness of this task, they will correctly conclude, “that it is nearly impossible to present a convincing comparison of the two authors.” His main reason for this pessimism is that, when comparing the two figures, one compares something called “Paul” to something called “Matthew.” These two entities that are being compared would then be the result of the breadth of scholarly consensus that has developed, but, he then claims that this difficulty is only exacerbated by the state of “post-concensus” that New Testament studies now finds itself in, that is, scholarship in both fields is splintered.

He then turns to the work of one scholar in particular, David Sim, who has argued for an explicit offensive attack on the communities that have formed around the theology contained through interpreting Paul’s letters. The reason for using Sim as an example of failing to grasp the difficult synthetic process is, “Sim is apparently making it fashionable again to claim that Matthew was directly attacking Paul.” He claims Sim’s aforementioned thesis requires the reader, “to agree to several controversial conclusions ― built on a growing mound of educated guesses ― about both Paul and Matthew.” (Unfortunately for Willits’ reader he does not give an example of one of these controversial conclusions.) Willits claims that Sim needs to get his portrait of Matthew and Paul exactly right before this task of synthesis is even started or the hostility will, “disappear like the Wicked Witch of the West.”

Having stated his doubts about comparing Paul and the Matthew, he then goes on to claim a certain type of comparison, i.e., descriptive, may actually be instructive. By this term, descriptive, he appears to means that Paul and Matthew can be compared for similarities. He then gives his crucial methodological principle, “the interpreter must limit herself primarily to the descriptive task and resist the urge to draw speculative conclusions.”

b. Paul and Matthew Within “Apostolic Judaism:” An Alternative Interpretative Framework

In this section, Willitts claims that he will provide a framework that is suitable for his desired descriptive comparison that is as accurate, “as possible with the socio-historical settings of the authors and documents in question.” For Willitts, the particular form of Judaism that Paul and Matthew were members of should be labeled apostolic Judaism, which like all forms of Judaism is Torah-observant. While he believes Matthew and Paul were both part of Judaism, he points out that there sect was not compatible with other forms of Judaism or, as he says, “apostolic Judaism was allogeneic.” He then claims that he is part of the “growing number of scholars” who believe the two should be viewed in this framework and that, “Paul’s letter’s were written to Gentile believers in Jesus within an ethnically diverse yet Jewish social setting, while Matthew’s Gospel was written to Jewish believers in Jesus with an ethnically restricted Jewish social context.” As for the supposed differences, they are the result of, “when Matthew and Paul address the same topic … they deal with it for different reasons and to accomplish different ends.”

c. Case Studies

He then turns to demonstrating how to properly compare Paul and Matthew. Before gives us the names of his test cases he pauses to tell us why he chose to employ these themes: 1) both authors unmistakably these traditions and 2) these traditions are obvious when a post-New Perspective framework is used. Also, it is important for his reader to know that he will not use detailed exegesis to come to his conclusions, instead, he will rely on the work of others that has already been done. (He claims that detailed arguments are “counterproductive and unnecessary!”) the authors in the areas of a) Davidic Messianism and b) Judgment according to works.

As for his claim that David Messianism is in Paul and Matthew, Willits shows that Rom. 1:1-6, 15:8-12 and Matthew 1 have been understood by some scholars to indicate that, “Davidic Messianism was basic to both Matthew and Paul.” If anyone objects because Matthew and Paul employ these themes in different manners, Willits answers, “my suspicion is that he would have used Davidic Messianisms as Matthew did, if he had written to the same audience for the same reason using the same genre.”

Next he discusses the theme of judgment according to works. He then turns to the work of Simon Gathercole and Roger Mohrlang. The work of these two scholars have shown that both Paul and Matthew employ texts from the Hebrew Scriptures (e.g., Prov. 24:12, Psalm 61.13) in their eschatological descriptions that envision a judgment according to works. Of course, Willits is careful to point out that Mohrlang denies that this judgment is salvific, but, if the believer does not have the proper works one may be disqualified. So, on the theme of judgment according to works, Willits believes that these two texts agree and are in sync with the Judaism from which they originated.

d. The Relationship Between Matthew and Paul

Having come to the conclusion that there is ample valid evidence for understanding Matthew and Paul as being in agreement on two major themes of the Judaism from which they emerged, Willits gives his take on how the two should be thought of as relating to one another. First, they should not be thought of as enemies because the Antioch Incident is no longer thought to reveal a break between the two strands of Christianity (i.e., Judaean and Hellenistic), plus, it is falling out of fashion to understand Matthew as having been written in Antioch. So, if there is no evidence to support a hostile relationship between the two authors (or, communities) then a cautious and careful scholar is left with two poles: 1) the two were unlike each other 2) the two were similar to each other. In the end Willits believes, “one can justifieably conclude that Matthew was either pro-Pauline … or un-Pauline.”

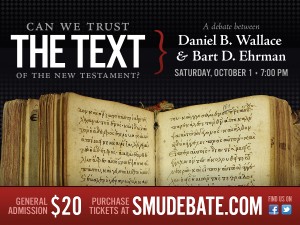

Rob Marcelo with Friends of CSNTM (Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts) said via facebook today: “Tickets are continuing to sell fast, and this is now going to be the largest single debate on the Reliability of the text of the New Testament in recorded history! Make sure to pick up your tickets soon at www.smudebate.com”

Rob Marcelo with Friends of CSNTM (Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts) said via facebook today: “Tickets are continuing to sell fast, and this is now going to be the largest single debate on the Reliability of the text of the New Testament in recorded history! Make sure to pick up your tickets soon at www.smudebate.com”

Before I get to my comments on Michael F. Bird’s article, I think it will be best to give my impression of his work in general so my remarks are not misconstrued. My first encounter with Dr. Bird’s work was in 2007, which was just about the time N.T. Wright’s influence in my thinking began to wane. I read Dr. Bird’s book on the righteousness of God and was very impressed by his research and judiciousness, even though I did not always agree with him. I then became a follower of the

Before I get to my comments on Michael F. Bird’s article, I think it will be best to give my impression of his work in general so my remarks are not misconstrued. My first encounter with Dr. Bird’s work was in 2007, which was just about the time N.T. Wright’s influence in my thinking began to wane. I read Dr. Bird’s book on the righteousness of God and was very impressed by his research and judiciousness, even though I did not always agree with him. I then became a follower of the