I was reading up on the interpretation of the “spirits in prison” passage in 1Peter 3:19-20 in John H. Elliott’s Anchor Bible Commentary when I realized that one of the primary interpretations held by the church fathers seemed to have been partially rooted in an extant OT textual tradition. As Elliott references a few texts from the fathers (particularly Irenaeus and Justin Martyr) to identify their interpretive tradition, he observes that in their addressing of the descent of Christ, they do not openly refer to or quote 1 Peter 3:19-20, but to a textual tradition seemingly shared by early fathers that is no longer attested to by any biblical manuscripts we have recovered thus far.

I was reading up on the interpretation of the “spirits in prison” passage in 1Peter 3:19-20 in John H. Elliott’s Anchor Bible Commentary when I realized that one of the primary interpretations held by the church fathers seemed to have been partially rooted in an extant OT textual tradition. As Elliott references a few texts from the fathers (particularly Irenaeus and Justin Martyr) to identify their interpretive tradition, he observes that in their addressing of the descent of Christ, they do not openly refer to or quote 1 Peter 3:19-20, but to a textual tradition seemingly shared by early fathers that is no longer attested to by any biblical manuscripts we have recovered thus far.

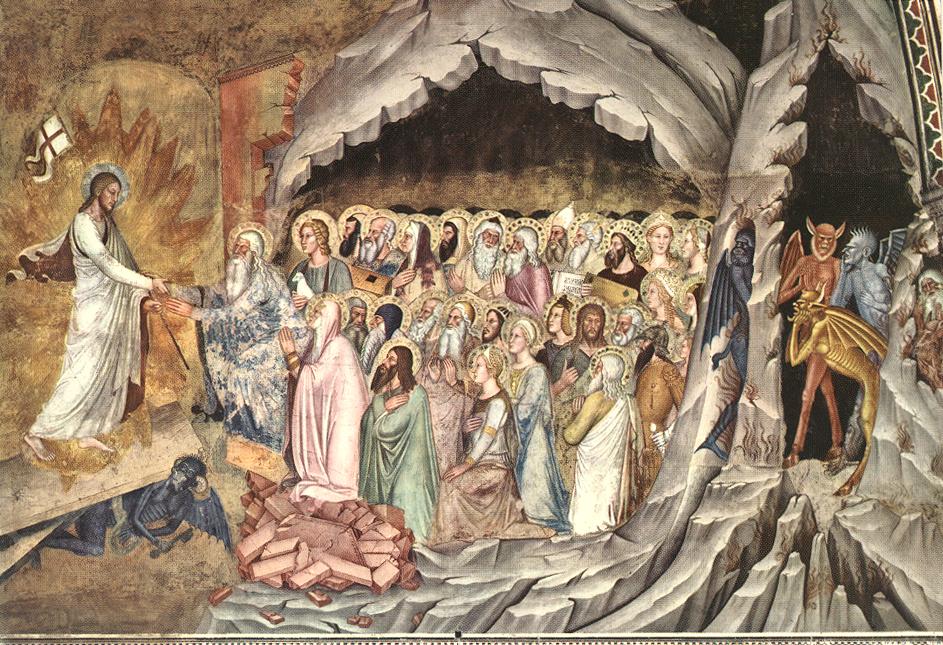

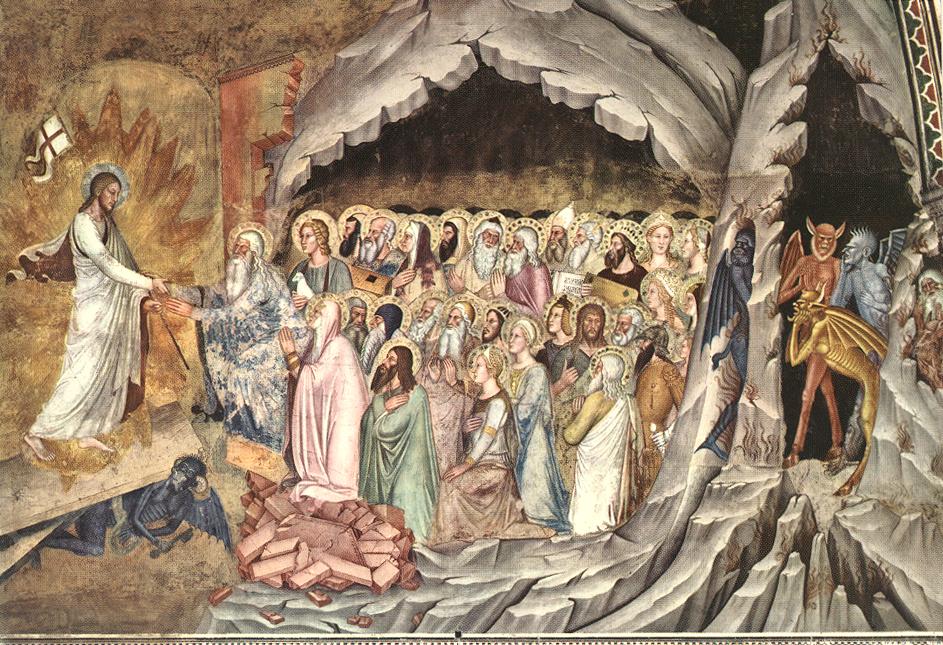

The view spoken of as espoused by these early fathers (as 1 Peter 3:19-20 has frequently been interpreted, even among later reformers such as Calvin) is as follows: when Christ descended (πορευθεὶς – having gone) to the realm of the dead upon His death before His resurrection, He in the spirit proclaimed good news to the righteous who perished before the flood (and in some cases all those faithful to God before Christ came) whose souls were imprisoned there to deliver them (most likely in conjunction with 4:6).

Oddly enough, though it may be in mind, this specific passage is not sited in defense of this view which some of the apostolic fathers clearly espoused but is supported by an unknown text attributed to Jeremiah (and also once to Isaiah by Irenaeus [Against Heresies 3.20.4]), referred to often by scholars as the “Jeremiah Logion”. We find this supposed lost textual tradition cited in Justin Martyr’s Dialogue with Trypho, 72. In context, Justin charges his Jewish interlocutor’s teachers with a most sweepingly general accusation that they have removed from the true scriptures, which Justin argues the LXX rightly represents or interprets. Trypho then asks for an exmaple of these alleged texts that have been removed by his Jewsih kinsmen who militantly appose the Christian faith. Justin gives two examples: one he says from Esdras and the other from Jeremiah. The supposed Jeremiah fragment is at the heart of our discussion. He says it read as follows:

“The Lord God remembered His dead people of Israel who lay in the graves; and He descended to preach to them His own salvation.” – Dial. 72

Interestingly enough, we see the same kind of quotation by Irenaeus in his Against Heresies in multiple locations at important theological intersects (3.20.4; 4.22.1; 4.33.1; 4.33.12; and 5.31.1). This supposed extant OT textual tradition seems to be a theological butress to Irenaeus’ understanding of the descent of Christ. In the very places you would expect him to default a quotation of 1 Peter 3:19-20, he does not, and instead supplies us with the same extant quotation. The citation is recorded in minor formulaic variations as follows:

“And the holy Lord remembered His dead Israel, who had slept in the land of sepulcher; and He came down to preach His salvation to them, that He might save them.” – Her. 3.20.4 (here Irenaeus claims this passage is from Isaiah)

“And the holy Lord remembered His dead Israel, who had slept in the land of sepulcher; and He descended to them to make known to them His salvation, that they might be saved.” – Her. 4.22.1 (here Irenaeus claims the passage is from Jeremiah, in congruence with the claim by Justin Martyr)

“The holy Lord remembered His own dead ones who slept in the dust, and came down to them to raise them up, that He might save them.” – Her. 5.31.1 (here Irenaeus states that “others”, in context speaking of the prophets, have said this, indicating he may of thought both prophets had recorded this sentence in its most rudimentary form)

It seems unlikely for the fathers to invent similiar passages to build a theology upon, especially as they are in context being used apologetically. Due to its frequent citation, its apolegetic usage, and its proposed deletion from manuscripts due to Jewish removal, this leaves us with the strong possiblity of the previous existence of an extant LXX tradition that provides seemingly adequate support for a possible view regarding the descent of Christ.

A long awaited seminar class is finally underway in the Criswell College New Testament department entitled “Christology and Monotheism“. This is not a systematic theology class, nor a class reading the early christian creeds back into the text, but is a seminar exploring the early Jewish background to the Christology of the NT. I have been waiting patiently for a formal class on this particular topic for a couple of years and I am enlivened at the opportunity to delve into the Second Temple Jewish conception of the heavens and their populace for backgrounds of our understanding of how the NT authors articulate their comprehension of Jesus of Nazereth, who is called Son of God, Son of Man, Lord, Messiah, the Great High Priest, and even God.

A long awaited seminar class is finally underway in the Criswell College New Testament department entitled “Christology and Monotheism“. This is not a systematic theology class, nor a class reading the early christian creeds back into the text, but is a seminar exploring the early Jewish background to the Christology of the NT. I have been waiting patiently for a formal class on this particular topic for a couple of years and I am enlivened at the opportunity to delve into the Second Temple Jewish conception of the heavens and their populace for backgrounds of our understanding of how the NT authors articulate their comprehension of Jesus of Nazereth, who is called Son of God, Son of Man, Lord, Messiah, the Great High Priest, and even God.

I was reading up on the interpretation of the “spirits in prison” passage in 1Peter 3:19-20 in John H. Elliott’s Anchor Bible Commentary when I realized that one of the primary interpretations held by the church fathers seemed to have been partially rooted in an extant OT textual tradition. As Elliott references a few texts from the fathers (particularly Irenaeus and Justin Martyr) to identify their interpretive tradition, he observes that in their addressing of the descent of Christ, they do not openly refer to or quote 1 Peter 3:19-20, but to a textual tradition seemingly shared by early fathers that is no longer attested to by any biblical manuscripts we have recovered thus far.

I was reading up on the interpretation of the “spirits in prison” passage in 1Peter 3:19-20 in John H. Elliott’s Anchor Bible Commentary when I realized that one of the primary interpretations held by the church fathers seemed to have been partially rooted in an extant OT textual tradition. As Elliott references a few texts from the fathers (particularly Irenaeus and Justin Martyr) to identify their interpretive tradition, he observes that in their addressing of the descent of Christ, they do not openly refer to or quote 1 Peter 3:19-20, but to a textual tradition seemingly shared by early fathers that is no longer attested to by any biblical manuscripts we have recovered thus far. I saw Robert S. Fyall’s book, “Now my Eyes have seen You: Images of creation and evil in the book of Job” sitting on my roomates shelf, probably due to my constant talk about creation and the waters. This book is part of the “New Studies in Biblical Theology” series edited by D. A. Carson. A fine addition this makes to the series, unique due to the topic. I thoroughly enjoy any scholarly work done in this area of study (as seen previously by my Levenson post) but this one stood out a bit. The way in which Fyall deals with the sea motif in his forth chapter (“The Raging Sea“), first the texts in Job and then subsequently relating it to the calming of the sea by Jesus in the gospels will be illuminating for many who have not studied the topic (this book having been written primarily for evangelicals). He interracts with the best scholars in the respective fields and deals judiciously with previous work on the topic. I recommend it for those who are interested with OT themes of creation, the Leviathan/sea problem, and God’s dealings with evil.

I saw Robert S. Fyall’s book, “Now my Eyes have seen You: Images of creation and evil in the book of Job” sitting on my roomates shelf, probably due to my constant talk about creation and the waters. This book is part of the “New Studies in Biblical Theology” series edited by D. A. Carson. A fine addition this makes to the series, unique due to the topic. I thoroughly enjoy any scholarly work done in this area of study (as seen previously by my Levenson post) but this one stood out a bit. The way in which Fyall deals with the sea motif in his forth chapter (“The Raging Sea“), first the texts in Job and then subsequently relating it to the calming of the sea by Jesus in the gospels will be illuminating for many who have not studied the topic (this book having been written primarily for evangelicals). He interracts with the best scholars in the respective fields and deals judiciously with previous work on the topic. I recommend it for those who are interested with OT themes of creation, the Leviathan/sea problem, and God’s dealings with evil. “Creation and the Persistance of Evil: The Jewish Divine Drama of Omnipotence” has, I have to say, become one of my favorite books in OT Studies. The reason I say this is because it opened up my conservative evangelical mind to the reality of some difficult things in the OT. Granted many conclusions or interpretive decisions that are made in the book may be called into question, he deals with many themes in the Hebrew scriptures that are often read over by mainline evangelicals which are critical to OT theology. Not only this, but the book will help all those who are unfamiliar with the warfare motifs in apocalyptic literature and allow them to begin making connections, not only in the OT genre, but in NT apocalyptic as well. Theologically the Christian may run into some difficulties, but keep the big picture in mind. Levenson is certainly a creative thinker but this is a very important book and there is much to be gleaned from it in terms of the mythopoeic background for many of the polemics in the Hebrew Bible.

“Creation and the Persistance of Evil: The Jewish Divine Drama of Omnipotence” has, I have to say, become one of my favorite books in OT Studies. The reason I say this is because it opened up my conservative evangelical mind to the reality of some difficult things in the OT. Granted many conclusions or interpretive decisions that are made in the book may be called into question, he deals with many themes in the Hebrew scriptures that are often read over by mainline evangelicals which are critical to OT theology. Not only this, but the book will help all those who are unfamiliar with the warfare motifs in apocalyptic literature and allow them to begin making connections, not only in the OT genre, but in NT apocalyptic as well. Theologically the Christian may run into some difficulties, but keep the big picture in mind. Levenson is certainly a creative thinker but this is a very important book and there is much to be gleaned from it in terms of the mythopoeic background for many of the polemics in the Hebrew Bible. When reading the Apostolic Fathers such as 1 Clement as a biblical studies student, my first knee jerk reaction is to read it with the excessively critical lenses of one who is searching for theological trajectories that can be traced from the scriptures to these deuterocanonical texts and do comparative work in order to be able to say something about the authorial conception of God. Last night, to my own amazement I must admit, I did not read the text in this way. I just layed back comfortably in my bed, tired from a long day, and said “hey, why not read some 1 Clement (if you are thinking random, I know)?”

When reading the Apostolic Fathers such as 1 Clement as a biblical studies student, my first knee jerk reaction is to read it with the excessively critical lenses of one who is searching for theological trajectories that can be traced from the scriptures to these deuterocanonical texts and do comparative work in order to be able to say something about the authorial conception of God. Last night, to my own amazement I must admit, I did not read the text in this way. I just layed back comfortably in my bed, tired from a long day, and said “hey, why not read some 1 Clement (if you are thinking random, I know)?”

Hope is a hard commodity to come by these days. In a time of economic “crisis”, political turmoil, unstable foreign relations, and even war, many Evangelical Christians have a hard time believing that they have anything to say to the lost and dying world in regards to supplying this precious commodity in the present. After talking to many of these Christians, many tend to retreat to the idea that “well, we will all go to heaven when we die” as if to escape any glimpse of this precious commodity we call hope in the present life. We try to muster up enough looking towards a relatively uncertain post-mortem state in the place we call “heaven” leaving the world to its demise. As Christians with a hope resembling that of a battered child we pray our Presidents and politicians we vote in can give us a glimpse of this precious commodity by implementing policies that will somehow help the nation we live in with its socio-economic and moral distresses. The on-looking pagan world looks for hope and hears of a far off gospel about going to heaven when we die, looks around at the world around them, and sees little need to believe in that which has no real power to change the world. In the Southern Baptist Convention of which church I have been a part of, our own Baptist Faith and Message seems to agree with this frail line of thought. Article 10 on last things reads as such:

Hope is a hard commodity to come by these days. In a time of economic “crisis”, political turmoil, unstable foreign relations, and even war, many Evangelical Christians have a hard time believing that they have anything to say to the lost and dying world in regards to supplying this precious commodity in the present. After talking to many of these Christians, many tend to retreat to the idea that “well, we will all go to heaven when we die” as if to escape any glimpse of this precious commodity we call hope in the present life. We try to muster up enough looking towards a relatively uncertain post-mortem state in the place we call “heaven” leaving the world to its demise. As Christians with a hope resembling that of a battered child we pray our Presidents and politicians we vote in can give us a glimpse of this precious commodity by implementing policies that will somehow help the nation we live in with its socio-economic and moral distresses. The on-looking pagan world looks for hope and hears of a far off gospel about going to heaven when we die, looks around at the world around them, and sees little need to believe in that which has no real power to change the world. In the Southern Baptist Convention of which church I have been a part of, our own Baptist Faith and Message seems to agree with this frail line of thought. Article 10 on last things reads as such: