So in the process of doing research for a paper, I kept coming across early Christian paintings of Jonah and the Great Fish. The first thing I thought was that these paintings look nothing like the Jonah inscription on ossuary 6 from Talpiot Tomb B. I also noticed that this was a popular story. It is reproduced throughout the vast catacomb networks in Rome and also on sarcophagi. For the most part, the images looked the same. And many of these images told the story of Jonah being eaten by the fish, Jonah being spit out by the fish, and Jonah resting on dry land, usually under a plant/tree or a vine.

The first thing I thought was that these paintings look nothing like the Jonah inscription on ossuary 6 from Talpiot Tomb B. I also noticed that this was a popular story. It is reproduced throughout the vast catacomb networks in Rome and also on sarcophagi. For the most part, the images looked the same. And many of these images told the story of Jonah being eaten by the fish, Jonah being spit out by the fish, and Jonah resting on dry land, usually under a plant/tree or a vine. The theme of this story is the deliverance of God; apropos as it is painted in tombs and inscribed on sarcophagi. There was one particular painting of the story of Jonah, though, that caught my eye. Like the others, the the depiction of Jonah and the Great Fish in the Catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus is told in three scenes, but with one big difference. While Jonah (as an orant) is eaten by the fish in the first scene and Jonah is resting in the third scene, this fourth century artist has replaced the the middle scene with a depiction of Helios riding through the heavens on his horse drawn chariot!

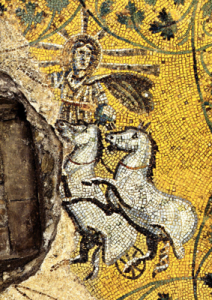

The theme of this story is the deliverance of God; apropos as it is painted in tombs and inscribed on sarcophagi. There was one particular painting of the story of Jonah, though, that caught my eye. Like the others, the the depiction of Jonah and the Great Fish in the Catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus is told in three scenes, but with one big difference. While Jonah (as an orant) is eaten by the fish in the first scene and Jonah is resting in the third scene, this fourth century artist has replaced the the middle scene with a depiction of Helios riding through the heavens on his horse drawn chariot! This isn’t actually a depiction of Helios, though. This is simply how Helios is depicted in pagan art; he rides his chariot across the heavens during the daily cycle. The nimbus behind the figure on the chariot in the Jonah story suggests there is some type of divine status to be applied to him (although I’m curious why its blue and not yellow/gold). Perhaps this is a painting of Jesus riding the chariot through the heavens. Perhaps the symbolism behind this painting is the hope of apotheosis of the deceased. The Helios symbolism is also found in a tomb under St. Peter’s Basillica. This third-century painting has been dubbed the Christ-Helios.

This isn’t actually a depiction of Helios, though. This is simply how Helios is depicted in pagan art; he rides his chariot across the heavens during the daily cycle. The nimbus behind the figure on the chariot in the Jonah story suggests there is some type of divine status to be applied to him (although I’m curious why its blue and not yellow/gold). Perhaps this is a painting of Jesus riding the chariot through the heavens. Perhaps the symbolism behind this painting is the hope of apotheosis of the deceased. The Helios symbolism is also found in a tomb under St. Peter’s Basillica. This third-century painting has been dubbed the Christ-Helios.

In the same tomb there is a picture of Jonah being tossed off a boat and into the mouth of a great sea monster. God as deliverer in Christ seems to go well with the Jonah story.

In the same tomb there is a picture of Jonah being tossed off a boat and into the mouth of a great sea monster. God as deliverer in Christ seems to go well with the Jonah story.

The use of Helios imagery was also used in Jewish synagogues (Hammat Tiberias [4th/5th c.], Sepphoris [5th c.], Beth Alpha [6th c.]). In the synagogue, though, Helios is inside the zodiac and the personified seasons occupy the corners. The central figure riding the chariot has been interpreted many ways. Some take it to represent God himself (Goodenough), Elijah (Waden), or Metatron (Magness) Christians also followed suit (or vise versa), though. At the Monastery of the Lady Mary in Beth Shean the 6th century zodiac appears on a floor mosaic, where a personified Helios and Selene are at the center. I would be interested to read the interpretations on that mosaic! In light of all of this, a couple things are striking to me. First, the Jonah and the Great Fish depictions in 3rd and 4th century  Christian art look nothing like that which is proposed to be on ossuary 6 at the Talpiot tomb. Second, it is interesting that pagan symbols were borrowed so readily by both Jews and Christians. I say, “readily” because there is a host of other pagan symbols used throughout the Christian catacombs and in synagogues. This has certainly caused me to reconsider the weight of the authority behind written material:

Christian art look nothing like that which is proposed to be on ossuary 6 at the Talpiot tomb. Second, it is interesting that pagan symbols were borrowed so readily by both Jews and Christians. I say, “readily” because there is a host of other pagan symbols used throughout the Christian catacombs and in synagogues. This has certainly caused me to reconsider the weight of the authority behind written material:

“All images are forbidden because they are worshiped [at least] once a year. So says R. Meir. But the sages say: ‘Only that is forbidden which holds a staff or a bird or a sphere in its hand.’ R. Simeon b. Gameliel says: ‘Anything holding an object is forbidden.’ (m. Abod. Zar. 3.1)