A few weeks ago, I decided to see how some non-academic Christians would respond to the possibility of YHWH being the referent to Paul’s claim that ο θεος του αιωνος τουτου has blinded the minds of the unbelievers. I presented this possibility in a weekly Bible study that I lead at the church I used to pastor. Long story short, it didn’t go well. Actually, that’s not accurate; it was a disaster. Not only did none of the attendees agree that this was right none of them were even willing to consider it.

(Just like, IMHO, some in the recent blogsphere who have completely overreacted to our current favorite pastor with foot-in-mouth disease’s comments regarding God hating people.)

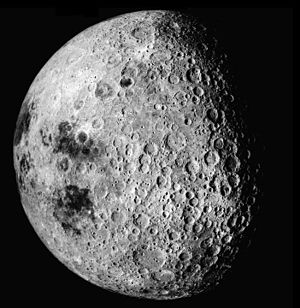

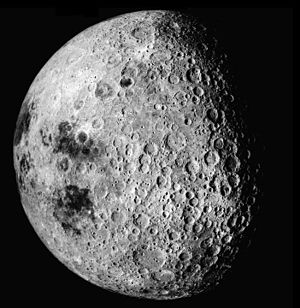

Apparently, God’s love is so important that to talk of Jesus’ father blinding people so that they won’t see bordered on heresy. It is like everyone gladly acknowledges, in theory, God’s hatred of things (or people) yet we must never speak of it; It’s there but never comes into play — like the dark side of the moon. This hermeneutical insistence among Christians (that I know either personally or through forms of media) has always puzzled me.(I can’t think of a way that deliverance can be accomplished apart form judgment.) But, since I do not share the need to expunge hatred from God I will present the case for YHWH (or Jesus’ Father) as being the referent for this phrase. (Please note: I am not saying YHWH has to be the referent but, he could be the referent.)

Apparently, God’s love is so important that to talk of Jesus’ father blinding people so that they won’t see bordered on heresy. It is like everyone gladly acknowledges, in theory, God’s hatred of things (or people) yet we must never speak of it; It’s there but never comes into play — like the dark side of the moon. This hermeneutical insistence among Christians (that I know either personally or through forms of media) has always puzzled me.(I can’t think of a way that deliverance can be accomplished apart form judgment.) But, since I do not share the need to expunge hatred from God I will present the case for YHWH (or Jesus’ Father) as being the referent for this phrase. (Please note: I am not saying YHWH has to be the referent but, he could be the referent.)

Exhibit A for the current case must be the OT witness of God’s character. First, I must assert that the OT (or the NT, or any other non-canonical literature that I am aware of) EVER claims that YHWH loves everyone at all times in such a way that judgement is never an option. Actually, the opposite is clearly true. (For a particularly blunt statement see Prov 1[1].) While one could mention many passages, it seems that Isaiah 6:9, 10 are the most pertinent verses for the matter at hand.

9 And he said, “Go and say to this people:

‘Keep listening, but do not comprehend;

keep looking, but do not understand.’

10 Make the mind of this people dull,

and stop their ears,

and shut their eyes,

so that they may not look with their eyes,

and listen with their ears,

and comprehend with their minds,

and turn and be healed.”

Here, we find YHWH commissioning Isaiah the prophet with a message that appears to have no redemptive value whatsoever. The message, it says in verse 10, is to have the result that those who hear his message (this people) will NOT be repentant and thus be forgiven. On top of that, when Isaiah asks YHWH the duration of this negative purpose he is told that it will be, “until the LORD sends everyone far away,” and if anyone remains, “it will be burned again.” So, we have a very clear text that indicates the God of the Scriptures is very capable of hindering individuals from salvation.

Before moving on, I would like to mention some things about this passage that will aid one coming to a proper interpretation. The book of Isaiah seems to make clear that Isaiah did not always understand this as his purpose. Indeed, he attempted to persuade people to trust God. This language appears to be technical language for judgment or, to put it another way, they were no longer going to be given time to change their ways. God had reaching the point of no return with Israel (especially the leaders) and they were going into Exile for their idolatry.[2] In other words, it does not necessarily indicate that YHWH wanted every single person to be kept from repenting but that the nation’s fate was sealed. It also does not necessarily indicate every single Israelite was idolatrous.

Another text that is worth noting is found in Deuteronomy 29:2 − 4. It says:

Deut. 29:2 Moses summoned all Israel and said to them: You have seen all that the LORD did before your eyes in the land of Egypt, to Pharaoh and to all his servants and to all his land, 3 the great trials that your eyes saw, the signs, and those great wonders. 4 But to this day the LORD has not given you a mind to understand, or eyes to see, or ears to hear.

In this passage we have a text that has YHWH claim that the Israelites needed YHWH to give them the ability to understand, see and hear (i.e., in a salvific way). This would seem to contradict the clear requirement of Deut’s message: Obey! But, the more likely understanding of this passage is to understand the verse as and editorial aside that is meant to be understood as, “Until this day, that is, until the day of the reader, the LORD…”[3] So, the statement was a retrospective observation about the reality of Israel’s past spiritual condition. This verse along with the previous interpretation, really make sense if one sees Paul alluding to this verse in 2Cor 3:12 − 15, which says,

“… Moses, who put a veil over his face to keep the people of Israel from gazing at the end of the glory that was being set aside. But their minds were hardened. Indeed, to this very day, when they hear the reading of the old covenant, that same veil is still there, since only in Christ is it set aside. Indeed, to this very day whenever Moses is read, a veil lies over their minds;”

If the previous interpretation of the Deut. 29 is what Paul had in mind when he wrote 2Cor then things begin to make sense. Exodus demonstrates that Israel’s Wilderness Generation was hardened, in that they did not trust YWHW, and Deut claims that “to this day [of the reader which is now up to the time of Paul]” Israel still could not trust their God [in a salvific way].

If all of this is true, (I am persuaded of this!) then it would make YHWH as the referent of the phrase in question very possible.

[1] “Because I have called and you refused, have stretched out my hand and no one heeded, and because you have ignored all my counsel and would have none of my reproof, I also will laugh at your calamity; I will mock when panic strikes you, when panic strikes you like a storm, and your calamity comes like a whirlwind, when distress and anguish come upon you. Then they will call upon me, but I will not answer; they will seek me diligently, but will not find me.”

(Proverbs 1:24–28 NRSV)

[2] For a full discussion of this see, “A Foundational Example of Becoming Like What We Worship.” In We Become What We Worship: A Biblical Theology of Idolatry, 37-70. Downer’s Grove: IVP Academic, 2008.

[3] For a full explanation see Biddle, Mark. Deuteronomy. Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary. Smyth & Helwys Pub, 2003, 438.

Apparently, God’s love is so important that to talk of Jesus’ father blinding people so that they won’t see bordered on heresy. It is like everyone gladly acknowledges, in theory, God’s hatred of things (or people) yet we must never speak of it; It’s there but never comes into play — like the dark side of the moon. This hermeneutical insistence among Christians (that I know either personally or through forms of media) has always puzzled me.(I can’t think of a way that deliverance can be accomplished apart form judgment.) But, since I do not share the need to expunge hatred from God I will present the case for YHWH (or Jesus’ Father) as being the referent for this phrase. (Please note: I am not saying YHWH has to be the referent but, he could be the referent.)

Apparently, God’s love is so important that to talk of Jesus’ father blinding people so that they won’t see bordered on heresy. It is like everyone gladly acknowledges, in theory, God’s hatred of things (or people) yet we must never speak of it; It’s there but never comes into play — like the dark side of the moon. This hermeneutical insistence among Christians (that I know either personally or through forms of media) has always puzzled me.(I can’t think of a way that deliverance can be accomplished apart form judgment.) But, since I do not share the need to expunge hatred from God I will present the case for YHWH (or Jesus’ Father) as being the referent for this phrase. (Please note: I am not saying YHWH has to be the referent but, he could be the referent.)